Apologist Erik Strandness ponders on an important topic that can be ignored in the debate over ‘universalism’ – what we are to be saved from - the reality of sin and Jesus’s central role in its defeat

Premier Unbelievable hosted a recent debate about “universal salvation” that caused me to reflect on the roots of what we must be saved from and the choices that must be required. The conversation, “Is God’s love truly for all - universalism or eternal damnation?” between Princeton Theological Seminary student Andrew Hronich, author of the new book “Once loved always loved: The logic of apokatastasis,” and Professor of Philosophy Jerry Walls, author of “Hell: The logic of damnation.” It was a fascinating discussion moderated by the always thoughtful Sean McDowell.

Costly grace

McDowell began the conversation by making sure the guests agreed upon the definitions of salvation that would be used during the discussion. While these definitions certainly helped me understand each one of the possible soteriological permutations, unfortunately it left undefined the very sin from which they argued we were either universally or conditionally saved. The reason that understanding sin is so important to this discussion is because salvation isn’t just a golden ticket we find inside a Christian chocolate bar, but an atonement purchased at a very high price. If God had to empty himself and suffer and die on a Roman cross, then salvation isn’t cheap, and any discussion about it must count the cost. Dietrich Bonhoeffer made this point when he distinguished between cheap and costly grace:

“Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate…Costly grace is the gospel which must be sought again and again and again, the gift which must be asked for, the door at which a man must knock. Such grace is costly because it calls us to follow, and it is grace because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ. It is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life. It is costly because it condemns sin, and grace because it justifies the sinner. Above all, it is costly because it cost God the life of his Son: “ye were bought at a price,” and what has cost God much cannot be cheap for us. Above all, it is grace because God did not reckon his Son too dear a price to pay for our life, but delivered him up for us.”

Postmodern winter

Sin is a word that has been removed from the cultural lexicon because it is perceived as mean and judgmental. It seems that postmodernists believe it is a verbal violation of our linguistic safe space, a microaggression offending our supersized sense of self-worth. They not only believe that words, like sticks and stones, can break your bones, but also believe that words can kill, and find “sin” to be particularly lethal. Interestingly, St Paul shares this postmodern sentiment by acknowledging that sin is indeed toxic, but isn’t afraid to use the word in polite company, because he knows the consequences of not saying its name are quite severe.

Paul refers to sin as the sting of death, but how could death possibly sting any more than it already does? The reason is that at death our temporary mortal existence becomes locked into one of two eternal pathways - eternity with God in the new heaven and earth without tears and pain - or eternal separation from God with endless weeping and gnashing of teeth. Death brings us to a fork in the salvation road where we need to make a choice, this choice, however, isn’t as simple as repenting of our sins but must also include the decision to avail ourselves of the work of Christ. We don’t just say “I’m sorry” but must confess with our mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in our heart that God raised him from the dead. In other words, our afterlife destination requires a choice.

Sin is a scary word for those who live in the moment because it asks them to ponder what comes next. It requires one to honestly assess where they are, where they have been and contemplate where they may be going.

Read more:

Life, Death, and Sacrifice

Is there a rebirth of belief in God?

Abortion through the eyes of a neonatal physician

Does deconstruction signal the death of faith?

You are that man (or woman)

If you were to do a random “man on the street” interview and ask if there was something wrong with the world, you would get a unanimous “yes.” If you then pushed them to identify the culprit, they might implicate republicans, democrats, capitalists, socialists, Christians, atheists etc, etc.. There is a common thread: the world has a problem, and the problem is humans. We can go on endlessly pointing our finger at others, but once we encounter our inner Nathan, we must admit that we “are that man.”

Sin, at its most basic level, informs us that “something” is wrong with the world, and that “something” is humans, and it this realization that motivates every government and religion to offer a fix. Sadly, they rarely deal with the root cause, and spend all their time trimming the consequential branches. I think one could argue that if you remove humans from the planet, it will probably continue to spin in a “good” way, but without people, it will never rotate to its “very good” potential. Humans bring something to the table that no other creature does but with great power comes great responsibility. Sadly, instead of accepting our role as stewards, we tried to became sovereigns. Instead of middle managing God’s creation we tried to oust the CEO, but in the process we only succeeded in elevating ourselves to our level of incompetence.

Human Pantheon

We don’t blame tornadoes, earthquakes and floods, or blame lions and tigers and bears for the problems in the world but point our fingers at humans. Interestingly, we accuse our fellow man of being super-villains while simultaneously believing they should act like superheroes. The Bible explains this by pointing out that we bear God’s image and have a unique place in the world, but that imprimatur also makes us prone to believing we are all that and a bag of divine chips.

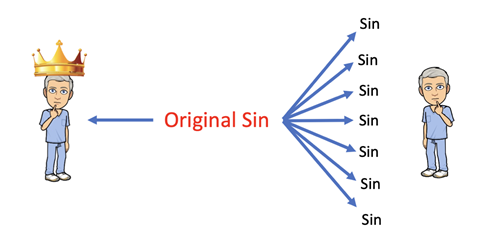

We tend to see sin as a cornucopia of bad behavior rather than the primal indigestion experienced by eating one bad fruit. We look at all our evil deeds and are ashamed but forget that it was our choice to be God-like that made them all possible. We need a root cause analysis of sin and not an invoice of consequences.

In the Genesis account of creation, God placed the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the center of the garden and warned Adam and Eve to not take of its fruit. The phrase good and evil is a merism which uses extremes to refer to a totality, much like heaven and earth is used to refer to all of creation. So, in other words, the tree represented what it meant to be God and have compete knowledge and served as an arboreal dividing line between Creator and created which when crossed would disturb the entire cosmic ecosystem.

If I am correct in my diagnosis of the sinful human condition, then before we ask who gets saved, we need to ask how salvation is even possible?

Celestial chutzpah

If the original problem was the temptation to be like God, then the way to reverse it would be to choose not to be God. A bad choice got us into trouble, so it would appear that a good choice would make it right. Our image bearing gives us the desire to do what is right, but our fallen nature makes us choose to do what is wrong. St. Paul says that the reason for our bad behavior is sin living in us: “I want to do what is good, but I don’t. I don’t want to do what is wrong, but I do it anyway. But if I do what I don’t want to do, I am not really the one doing wrong; it is sin living in me that does it.” (Romans 7:19-20, NLT)

What does it mean for sin to live in us? If we go back to the original sin of Adam and Eve, I think we can see that the cascade of bad behavior started with the belief that mere mortals could be God, therefore, the sin living within us is our penchant for celestial chutzpah. I think one could argue that Jesus didn’t just die for a series of indiscretions, but to reverse the original sin of trying to be like God.

Pro choice

I find it interesting that Jesus, like Adam and Eve, also had to be tempted by Satan. Why couldn’t he just have been sacrificed for our sins? Why the temptation? I believe the reason is that Jesus, as the second Adam, had to reverse the poor choice to be like God of the first Adam. Jesus was tempted to act like God by turning stones into bread, ruling all the nations, and proving his invincibility, each of which he had every right to do but instead he humbled himself by obeying the word of God, worshiping God, and refusing to test God. He emptied himself and became a servant, which was the posture Adam and Eve should have taken in the first place. Adam and Eve were tempted to be what they could never be, but Jesus was tempted to be what he already was. I think one could argue that it is more difficult to restrain oneself from being what you are than to pretend to be something you aren’t. The improper choice that got Adam and Eve tossed out into the wilderness would be reversed by the proper choice of Jesus once again granting us access to the Garden.

Death of God

Jesus reversed the bad choice of Adam and Eve through his wilderness temptation, but he still needed to complete the task by taking on the consequence of their rebellion. God warned the first couple “you shall surely die” if they ate from the tree and it is this death that they brought upon the human race, which Jesus then reversed through his death and resurrection.

In order for us to participate in Jesus’ correct choice we are once again confronted by a profound arboreal decision but this time we are asked to choose the tree from which he hung. By dying with Christ, we also die to our divine aspirations and as such can once again enjoy God’s presence. When we are found in Christ, his choice becomes our choice, and the first couple’s bad decision making is forgotten. Interestingly, in the new heaven and earth there is no mention of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, only trees of life. By choosing the tree upon which Jesus was crucified we effectively felled the tree that caused our Fall, thereby rendering sin impossible in the life to come.

As the sons of Zebedee discovered, greatness in God’s kingdom is achieved by becoming a servant and not assuming the divine right of a king. There is only room for one God in the kingdom and through the work of Jesus we are freed from our divine pretensions. Heaven is a kingdom of willing servants beholden to a servant King, while Hell is a banana republic populated by tin-pot dictators who still think they are in charge,

Salvation, therefore, requires more than an apology for bad behavior but necessitates a choice and it is here that questions of universal salvation become problematic. If God had to be tempted, betrayed, and then suffer and die so that we could enter his kingdom, then we can’t minimise it by handing out free passes. If all Paul wanted to know was “Christ and him crucified” then maybe we should similarly narrow our salvation focus.

If God is going to honor our free will, then salvation is a choice. We can argue about whether that choice occurs in this life or postmortem or whether it requires a purgatorial spanking machine or not, but in either case it still requires a decision. And it doesn’t matter if we academically define that choice as libertarian or compatibilist, or if we are talking about limited or unlimited atonement, because Jesus told us to go to the ends of the earth and offer that choice to others. We can amuse ourselves by theoretically contemplating the heavens, but Jesus calls us to put boots on the ground and spread the gospel to Judea, Samaria and the ends of the Earth. If salvation is universal, then the Great Commission is reduced to virtue signaling, and the pain and suffering experienced by the early church is just a reflection of its masochistic tendencies. I would hope that everyone would choose Jesus but the possibility of not choosing him must also exist.

Get access to exclusive bonus content & updates: register & sign up to the Premier Unbelievable? newsletter!

No other name

As I think I have made clear, my concern with the belief in universal salvation is that I fear it doesn’t take the life, death and resurrection of Jesus seriously enough. If there is no other name by which we are saved then it would seem to me that who he was, what he did, and how he did it, constitutes the requisite informed consent necessary to make such a monumental decision. Salvation isn’t as simple as saying “I’m sorry” to the God most high, but necessitates choosing his Son hanging on a cross. Like the guests on the show, I hold out hope that Jesus will continue to knock on our doors, even after death, but believe that we still must choose to open it and let him in.

Jesus died for the sins of the entire world, so everyone is eligible for salvation. The offer is universal, but the appropriation is particular. God demonstrates no greater love by sacrificially dying for our sins, but love isn’t a one-way street, it isn’t generic good will, but is an offer that must be accepted if a true loving relationship is to be established. Hell isn’t a jail for people who misbehave but a smoky night club for philanderers who leave God’s love unrequited.

Salvation is a marriage proposal offered by a God who has promised to love us through richer and poorer, sickness and health. Stunningly, Jesus extends this invitation to us despite our checkered past, but we must still come to the altar and declare “I do” or “I don’t.”

God wishes that none should perish, and he loves the world so much that he sent his only Son to die for everyone’s sins. The deed is done, the door to heaven is open, but there is one caveat, we must acknowledge the Door Man. We cannot forget that the amount we spend on our salvation is quite minimal, but it cost Jesus everything. Salvation isn’t achieved by reading a theological manual but by entering into a love story with a God who first loved us.

Love at the crossroads

Jesus is our Christian distinctive, the cross is our cherished icon, Easter is our greatest holiday, and yet we try to out-God every other God by making him omni-salvific. We cannot elevate the salvation product while neglecting the pain, suffering and death that went into its making.

God is love. God so loved the world. People will know us by our love. Love isn’t the problem, but unrequited love is. The prompt for the show was: Does God truly love everyone? The answer is a hearty “yes”, but the real question is, will all people love him back?

The debate over universal salvation is an interesting one but one that must be approached with caution because we cannot let our intellectual rumination cause us to neglect the nutritive value of the gospel. While God wants us to contemplate heavenly things, we need to take all thoughts captive to Christ and remember that salvation requires that we choose Jesus.

Erik Strandness is a physician and Christian apologist who practiced neonatal medicine for more than 20 years and has written three apologetic books. Information about his books can be found at godsscreenplay.com