Apologist Joel Furches explains why he believes disagreement within the Church points to the credibility of Christianity

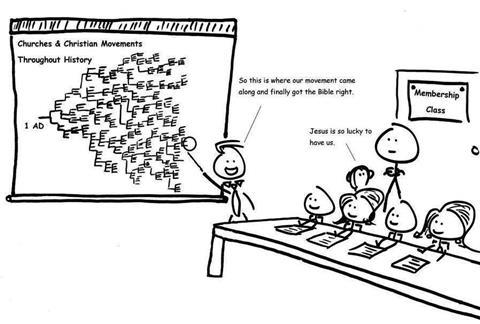

A whimsical cartoon shows a man standing in front of an elaborate chart. The chart begins with a single line which branches out into two lines. Those two lines branch out into several more, and so forth until the chart ends with hundreds of sub-branches of the original two. The man circles one of the many, many branches and states “…and this is where our church came along and set everything straight.”

This cartoon serves to illustrate one of the more awkward truths in the history of Christianity: the level of disagreement and the ever-expanding sub-divisions of authority over the 2,000-plus years of its history, speak of a lack of unity amidst those who all claim the same label. And whereas some members of Christendom might consider those with whom they disagree to be essentially under the same religious umbrella if, perhaps, slightly mistaken, others narrow down their doctrines to condemn all who disagree with them to be hell-bound heretics. Do these disagreements, from the subtle to the vast, serve as evidence against Christianity?

Read more:

Anything But God: Adrienne Johnson’s unlikely conversion to Christianity

Addressing abuse in the Church

How can Christianity be true when there are so many Church disagreements?

Church services can reach sceptics too

Truth and disagreement

It is worth noting at the outset that disagreement about the nature of a system does not falsify the system as a whole. Consider, for instance, the so-called Theory of Everything. In simple terms, the physics of the Universe seem vastly different in the grand scale described by Newton and in the fine details described by Einstein. For a very long time, physicists have tried to find a model that explains how everything works together as a whole.

Dozens of theories have been defended, including String Theory, M-Theory, Loop Quantum Gravity, Causal Sets and more. To say that the multitude of models proposed by physicists undercuts physics as a whole is probably not an idea anyone would entertain. Given the conflicting definitions, some or all of these models are incorrect or incomplete, however scientists recognise that the process of exploring and testing these models contributes to the advancement of science as a whole.

In many ways, this is an appropriate comparison. Should scientists ever arrive at a complete Theory of Everything, it would be one of the most significant achievements in history, as it would provide an almost complete description of how the physical Universe works, from the infinite to the infinitesimal, from the very beginning of time to any point in the infinite future.

Similarly, a comprehensive understanding of God, his relationship with the human race, his nature, actions and purposes, his revelations both cosmic and personal, and the purpose for which humanity exists would provide a complete description of the metaphysical universe from beginning to end, as well as the way in which each individual should live his or her life.

Mere Christianity

Scientists begin with a shared understanding that physical forces exist and are observed to operate in particular ways. The rest of the scientific process is an attempt to explain those observations. Similarly, Christians begin with a shared understanding that God exists, that he is in some way responsible for the creation of the Universe and of humans, that the Bible is important in some way and that Jesus arrived in history, made specific claims, died and then reportedly rose from the grave. The rest of theology has been an attempt to explain those understandings.

‘Mere Christianity’, a term coined by the great CS Lewis, refers to these basic understandings that tie all of Christendom together. Christians the world over may not agree on the nature of baptism, freedom of the will, communion, the purpose of the cross and so on – however, they do share the common understandings outlined above, and Lewis suggests that these commonalities are what unites Christians.

Get access to exclusive bonus content & updates: register & sign up to the Premier Unbelievable? newsletter!

The virtue of disagreement

It may be a common instinct to suppose that disagreement in any system – political, religious, scientific, philosophical or otherwise – is a detriment, not a strength. However, this proves not to be the case. Returning to science as an illustration, the history of science is a tale of error and disagreement. And yet, science has proven to be the most successful venture in human history. As counterintuitive as it may seem, science’s permission to disagree is one of the things which has made it so successful.

The image of Galileo standing before a counsel and being placed under house arrest for daring to propose a model of the Universe contrary to that of the Greeks is a familiar one burned into the mind of every school child. And yet, had Galileo not disagreed with the geocentric model of the Universe, progress would never have been made in understanding the Universe. Scientists regularly check one another’s work, repeat it, expand on it and hold one another accountable for their errors.

Similarly, on any given Sunday, one will find church attendees with their Bibles open on their laps following their ministers as they teach. The Western world has the great privilege of access to Bibles, such that the common person may read and study on their own rather than relying solely on religious authorities to dispense truth.

Ecumenism refers to the presence of a variety of churches and religious views in conversation with one another. Each system of doctrine is available to criticise and hold the others accountable, and the more available their ideas, the less a church is able to stray into religious tyranny, as other options are always available to the followers therein. If any church-goer is not satisfied with the teaching or operation of that church, the world is filled with alternatives. This forces churches to be responsible with the services and teachings they provide.

In fact, the availability of atheism may be argued to be a similar check against a myopic Christianity unable to support its views, check its doctrine or hold itself accountable, as it has to meet, grapple with and resolve the criticisms against it.

Disunity

Christians everywhere are frequently seen bemoaning the overall lack of unity in the Church. Disagreements abound and are deeply divisive on subjects such as baptism, communion, free will and spiritual gifts. This fact has also been used as evidence against the truth of the Christian worldview. If Christianity were true, wouldn’t every Christian think and believe the same?

In 1978, the People’s Temple community in Jonestown, Guyana decided to commit mass suicide. 909 of the members voluntarily took cyanide poison. Those who refused were murdered.

In March of 1997, 38 members of the Heaven’s Gate community ingested cyanide and arsenic because of their belief that to do so would place them on-board a UFO to another dimension.

In January of 1521, reformer Martin Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X because he refused to recant a number of statements in his writings that disagreed with the official teachings of the Catholic Church.

One of the founding and sustaining principles of the United States is that of the separation of church and state. This ideal was prompted by the tyranny the founding fathers saw in the state religions common all over Europe at the time. In the countries that practised state religion, every citizen of that country was required to be a member of the official Church of that particular country.

Moreover, the reigning sovereign of that country was often considered the head of the state Church such that they had absolute authority both in areas of government and religion.

In founding a republic, the founding fathers hoped to make the government accountable to the people rather than forcing the people to follow laws in which they had no say. Likewise, in establishing freedom of religion, they hoped to give each individual within the country the freedom to make considered decisions about their own personal beliefs instead of forcing them to embrace doctrines and ideas that they might find unreasonable or unconscionable.

Freedom of belief

The freedom each individual possesses to make decisions on what they believe is both a tremendous liberty and an awesome responsibility. On the one hand, the individual is allowed – nay, encouraged - to examine what they are being taught and to accept it or reject it as their own reason dictates. On the other hand, no individual has the excuse of simply having to go along with what they are taught and thereby remain unaccountable for the consequences of that teaching.

This personal responsibility for beliefs is encouraged and even commanded by scripture. In Acts 17, the Christian missionaries Paul and Silas arrive in the town of Berea and begin teaching about the resurrected Christ in the Jewish synagogue. Rather than simply accepting what they were being told, however, the Bereans searched through the Tanakh (the Hebrew scriptures) to see if what Paul and Silas were teaching was accurate to scripture. For this, the Bereans were called “noble.”

In the book of Philippians, this same Apostle Paul places the responsibility for salvation directly on the shoulders of the individual when he says: “…not only in my presence but much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling.” The Apostle John does the same when he says: “Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world.” Finally, in the book of Revelation, John relays a message to each of the major churches at the time, encouraging them for their virtues and holding them accountable for their errors.

The New Testament is replete with warnings against false teachers and commands that the individual is responsible for examining what they are being taught.

Disagreement is a symptom of ignorance, not of knowledge. If every individual was omniscient – knew all things that were true and believed nothing that was false – there would be no disagreement. Since this is not the case, since all people are deficient in knowledge to one degree or another, disagreement is a natural consequence of thinking – a person who is in agreement with all people is a person who does not exercise free thought.

If all Christians agreed all of the time, this would, in fact, be a warning sign against that belief system; just as it would if all scientists or all politicians were in 100 percent agreement all of the time. Groups that are in 100 percent agreement consist of one absolutely sovereign leader and a number of mindless followers. These groups are called cults, and they never end well.

Joel Furches is an apologist, journalist and researcher on conversion and deconversion, based in the USA