Nigerian pastor Hassan John reflects on the anti-Christian violence in his home country and considers the appropriate response

A report about the horrific violence in Nigeria was recently released by an All-Party Parliamentary Group for Freedom of Religion or Belief – Nigeria: Unfolding Genocide? Three Years On. Roger Bolton spoke to Archdeacon Hassan John from Jos, Nigeria about on-going Chrisitan violence in his country. Below is an edited extract of what Hassan John said on Unbelievable?. To watch the entire show, click here

Rising violence

Living in Nigeria, where violence against Christians and the Church became the norm in the last decade and where people driven by a radical ideology believe killing a Christian earns them a space in paradise, then staying alive at all costs also becomes the necessity.

I know many Christians who believe that every Christian has the right to self-defence and therefore has the right to attack and also kill anyone who threatens their existence.

For me, even as a pastor, this became more real, seeing people hacked to death on the streets, families wiped out and meeting and praying with so many widows and orphans. The death toll of Christians and churches attacked by Boko Haram Islamist terrorist Jihadi groups over time kept raising. Thousands of people, predominantly Christians, were killed. I have attended so many mass burials and stood over so many mass graves of women and children. Boko Haram became the deadliest in the world, according to the Global Index on terrorism. The divide and hate between Christians and Muslims in Jos got worse.

Read more:

What is Islam and how does it differ from Christianity?

The religious roots of the Ukraine invasion

Making sense of Old Testament violence

Can Islam overcome sexism and violence?

A call to arms?

St Finbarr’s Catholic Church in Rayfield, Jos, central Nigeria was bombed in March 2012, killing over 14 people. The suicide bomber drove a car to the gates and when he was stopped by the boy scout manning the gate, he detonated the bomb. We were in St Christopher’s Anglican Church, where I was preaching, less than half a mile away that Sunday morning, and the aftershock of the bomb shook the entire church building, rattling the glass windows.

We were all rattled for weeks after the explosion. Disaster seemed to be edging nearer to us and we didn’t know if we would be the next target. One of my church council members met me about three weeks or so after the attack on St Finbarr’s and suggested that we needed to get an Ak47 in our church. He had served as a chaplain in the army and would be in custody of the weapon in the church. The weapon would be used to bring down any suicide bomber approaching the church with a device and that could save a lot of lives. His was not a strange suggestion because we were aware that churches and mosques were arming themselves.

Through the week I pondered what the church elder said and it made sense to get a weapon. The Nigerian government had proved either incapable or unwilling to adequately and effectively deal with the Islamic terrorism in north-eastern Nigeria, which has now spread to most parts of the middle belt region of the country. I sat in front of my church looking across to the predominantly Muslim community, wondering if the chips are down whether they will also attack my church.

A little girl

A girl of about 7 came passing by selling groundnuts, which she carried on her head in a tray. I called her and bought some. It dawned at me that she was selling groundnuts when she should be in school. I asked her why and she said her parents couldn’t afford the fees. She said her father was dead and her mother couldn’t send her to school.

I asked her if she was willing to go to school and she said “yes”. I then asked her to go and tell her mother that I, the pastor of this church, will pay her fees. As the girl walked away, I thought it may be better to talk to her mother myself, so I followed her. It was after a few feet, as we walked towards the road that divided us from the Muslim community, that I realised the girl was a Muslim.

I hesitated a little, but not wanting the girl to think the pastor of the church was lying, I decided to follow her into the Muslim community, by now very anxious, knowing that a policeman was killed in the community not too long ago.

I walked with the girl to her house, but because I was male I was asked to stand outside while the Muslim community leader was consulted. He said he would get back to me and I quickly left.

After a week, the leader didn’t get back to me, and to ease my conscience and prove that at least I had tried, or perhaps to prove that the Muslims hate Christians, I sent someone to ask if the mother of the girl would accept my offer. She did.

Training

The community leader asked that I should meet the mother and tell her myself, so that she would meet the person paying her daughter’s school fees. The woman, who was carrying a baby on her back, got on her knees, as is the tradition in the community, to thank me. I was completely disarmed by her gentleness and outpouring of gratitude. She explained why she sent the girl to sell groundnuts – so the family could get some money for food.

I asked if she had any skills and she said “no”. I then promised to help train her in any skills she wanted and I extended the invitation to any other widow in the community. I was also happy to pay the school fees of their children as well. We set a weekend for the training.

On the first Saturday of the training, 15 Muslim women turned up. Weeks into the training the number of Muslim women grew, and I was able to convince Christian widows to join the group. In three months we had over 250 Muslim and Christian women and the Anglican Bishop of Jos, Most Rev Benjamin Kwashi, who I informed of the challenge I was facing, took over the paying of fees for over 145 Muslim children.

We slowly started building trust in the community. About a year into the training programme, on a Christmas eve, the leader of the Muslim community called me and said: “Reverend, I must confess that from the beginning we had our doubts and thought you had a hidden agenda to try to convert our women and children to Christianity. Others in my community believed you had other motives, but I insisted that we give you the benefit of the doubt. I have watched closely and I have seen the Christianity the British Christian missionaries from England showed when they brought the Church and education to our communities. We loved them and they cared for us. It was a selfless service and we thank you.”

He then presented me with a fat cow. “So that you people can celebrate the Christmas,” he said. I thanked him and protested that the cow be sold and the money given to the poor widows I was training but he wouldn’t hear of it. I reluctantly took the cow and presented it to our Christian community, who were still sceptical about the Muslims across the road. The relationship grew slightly better.

Get access to exclusive bonus content & updates: register & sign up to the Premier Unbelievable? newsletter!

Protection

A few months later, on a Sunday morning, some Muslim youths saw a young man approaching my church with what looked like an explosive device. They quickly alerted the security around the community and an anti-bomb squad was called to take the man and device away.

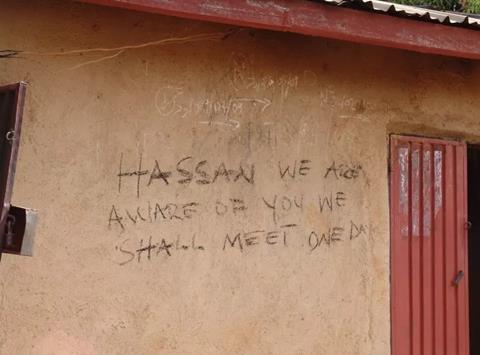

Immediately, the Muslim community leader sent for me. I went to him and he said: “Hassan, we, as a Muslim Community, have nothing to do with what just happened. The young man used to live among us but left many months ago. He must have been radicalised somewhere. Let me promise you Hassan that as long as we live in this community, nothing will ever happen to your church. We will protect your church because you have shown us love and care and it is our duty to protect your church. I promise you this, nothing will happen to your church.”

When I left him, it dawned on me, to my shame, that at some point I had wanted to get a gun to defend my church from these radical Islamists and this community. I wanted to use a gun, but through love and care, through a little girl selling groundnuts, we have made very good friends and built a caring relationship. The care we share has continued to grow over the years.

Archdeacon Hassan John is an Anglican priest, who comes from Jos, Nigeria. He is a church leader, campaigner for religious liberty and journalist. This is an edited extract of what Hassan John said on Unbelievable?. To watch the entire show, click here