Are science and religion in conflict? Is there more to life than mere matter? Where do we find meaning? Erik Strandness explores these big questions in light of a recent Big Conversation with atheist Philip Ball and Christian Nick Spencer

It is a widely held view that science and religion are in conflict, including and perhaps especially over how they approach one of life’s most fundamental questions: what does it mean to be human? But is that really the case? And do we need to rethink how we’ve been seeking the answer, at a time when we seemingly need more clarity over humanity’s identity than ever before?

Atheist science writer and broadcaster Philip Ball, author of The Book of Minds: Understanding Ourselves and Other Beings, From Animals to Aliens, recently engaged with Christian academic Nick Spencer, senior fellow at Theos and author of Magisteria: The Entangled Histories of Science & Religion. Click here to watch them discuss these important questions on The Big Conversation: Can science and religion tell us what it means to be human?

Here, Erik Strandness reflects on this topic and the recent Big Conversation.

What is man that you are mindful of him?

Christianity and science are often depicted as being at war with one another, but generally speaking they peacefully coexist because they are preoccupied with different questions. The religious contemplate the heavens while the scientist interrogates the Earth.

This truce, however, breaks down when they skirmish over the question of what it means to be human, because when the researcher becomes the researched and the theologian becomes the theologised, the findings have profound implications for free will, morality, equality and justice, all of which form the core of a civilised society.

This conflict is precipitated by the different ways this question is phrased. The believer asks God: “What is man that you are mindful of him?” While the atheist asks themselves: “What is man that we are mindful of him?”

“When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings, and crowned him with glory and honour. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet.” (Psalm 8:3-6)

When you eliminate spirit from the equation, you are left with only physical answers, which not only diminishes our human exceptionalism but gives us license to behave any way we want.

“When I look at the heavens and see the fall out of the Big Bang, the moon and star shrapnel scattered all about, I ask what is a human being? Does the Universe care? We have determined that he is a little higher than the great apes, the victor in the evolutionary battle. He has control of nature, and makes it bend to his will.” (Pscience 8:3-6)

I find it amusing that these in depth intellectual discussions about human exceptionalism are held in air conditioned studios with special microphones and lighting, the proceedings of which are then listened to by millions of people across the world on their computers and smart phones just before they head off to work in their electric cars to make technologically advanced widgets – and then, during a 15-minute coffee break, they briefly ponder whether they are smart monkeys or broken gods.

“Man had pre-eminence over all the brutes; man was only sad because he was not a beast, but a broken God.” (GK Chesterton)

Read more:

Is science at odds with religion?

‘Science is not enough’

A psychiatric nurse-turned practical theologian on suffering

Can a Quantum Physicist really believe in God?

Venn and the art of human maintenance

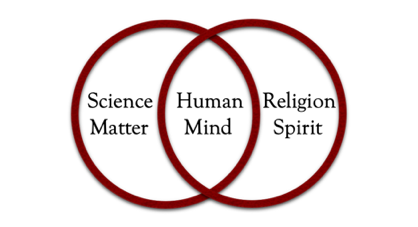

The late evolutionary biologist, Stephen Jay Gould coined the term ‘non-overlapping magisteria’ to create a truce between science and faith. He recognised that science was the expert on all things material while religion had become quite knowledgeable about the rules and regulations of the spiritual realm.

His tidy detente, however, falls apart when it comes to human nature because there is a profound overlapping of their magisterial claims. Humans, as it turns out, are the only creatures on the planet who think sequencing DNA and worshipping a God are both important endeavours. Sadly, this common ground, rather than start a conversation, turns into a war of words and the accusations fly as the materialist reduces religion to a God gene and the religious reissue scripture as a science textbook.

I practiced neonatal medicine for over 20 years and saw first-hand the limits of science. I saw glorious innovations that remarkably improved the care of neonates, but I also saw many drugs, theories and technologies fail miserably at the human bedside. Science helped me save lives, yet it slinked away when it failed, leaving me without any tools to treat the spiritual mess left in its wake.

My job was more than adjusting ventilator knobs, but also involved tending to the emotional and spiritual wounds opened by the death of a loved one. Gould’s theory of independent magisteria therefore falls apart when one goes from the bench to the bedside. I think it is quite telling that hospitals, centres of scientific excellence, feel the need to have pastors or priests on staff because it would seem to be a tacit admission that human exceptionalism is ultimately conferred by a heavenly stamp of approval and not by several million years’ worth of evolutionary merit badges.

(For more on pastoral and spiritual care, check out this episode of Unapologetic with John Swinton)

Genealogy of minds

Human nature is where the magisteria overlap and this is most powerfully demonstrated by debates over the nature of the mind, because the mind is the interface between the material and immaterial, the physical and spiritual, and the immanent and the transcendent. Atheist science writer and broadcaster Philip Ball, however, believes this interface is not as mysterious as the religious would have us believe because science has already documented a biological “genealogy of forms” and is rapidly closing in on the final frontier of human exceptionalism by filling in the details of a “genealogy of minds”.

In order to do this, however, one must view mind as a continuum from bacteria to blogger, differing in degree but not in kind. As Ball said on The Big Conversation: From bacteria upwards, a lot of biologists claim even single cell bacteria have to be thought about in cognitive rather than mechanistic terms.” The problem, as G.K. Chesterton pointed out, is that while a genealogy of forms may reveal biological variations on common themes, the mind of man stands alone as a unique innovation.

“There may be a broken trail of stones and bones faintly suggesting the development of the human body. There is nothing even faintly suggesting such a development of the human mind.” (GK Chesterton)

Ball pointed out that the way animals think is determined by the potentials and limitations of their body type. Thinking rises to the level of one’s biological competence, which explains the varying levels of mental capacity distributed throughout the animal kingdom. Birds don’t contemplate the life aquatic, and fish don’t wonder what it would be like to spread their wings. This idea, however, breaks down with humans because they push the biological boundaries by exploring the depths of the sea in submarines and flying around the world in airplanes.

“That an ape has hands is far less interesting to the philosopher than the fact that having hands he does next to nothing with them.” (GK Chesterton)

The materialist attempts to minimise the human mind by dousing every burning bush and replacing them with phylogenetic trees but ironically finds that increasing amounts of scientific data only serves to fan the flames of human exceptionalism.

Thinking outside the box

Ball noted that what had historically been taken for granted as exceptional in humans has become common place as science uncovers more and more similarities between human and animal thought and behaviour. So, instead of viewing the human mind as unique, he places it within a “space of all minds”, generously offering us a few select points between our animal ancestors and our future artificially intelligent robotic friends. The problem is that the human mind doesn’t like being confined to a space and is always thinking outside the box.

Humans are the only creatures capable of stepping outside the circle of life and observing it, measuring it, manipulating it and even writing songs about it. It appears that rather than being of like mind with animals, humans occupy a completely different headspace. Interestingly, humans observe the natural world and describe it as a circle of life but then live their lives as if they were vectors with magnitude and direction. Nature spins its wheels, but humans feel as if their lives are pointing somewhere which, inconveniently for the materialist, is most often heavenward.

Body of knowledge

We are currently experiencing a crisis of meaning but why should that be an issue for the most highly evolved creature if life is just about mutating and mating? Why would natural selection choose to add psychological baggage to a perfectly working physical system? Ball recognised the importance of meaning but once again had to situate it within a spectrum of animal abilities.

He explained meaning by appealing to a simple process of sorting environmental inputs into useful or useless categories with each new input making meaning more sophisticated. Meaning for Ball therefore is created piece by piece and not discovered. It is not unique to humans but is just found in a more highly evolved state:

“If science cannot say anything about the construction of meaning then there is a very important part of the experience that’s missing. And one thing I argue in the book is that minds are also about the construction of meaning, and by that I mean even at the very simple level that minds and bodies have evolved to take notice of some things and to ignore others. And those things it takes notice of are the things that, presumably, are most central to the persistence, the survival of the animal. So, that in a way is a construction of meaning in that it’s assigning value to some inputs coming in from the environment and not to others and one can argue that this is the beginning of a system of constructing value.”

Meaning, however, isn’t found in keeping the good and throwing out the bad, but by asking who it was that declared them good and bad in the first place. When humans step outside the space of possible minds, they aren’t just looking from the outside in but also from the top down and it is from this heavenly perspective that the Earth obtains meaning.

Animals spin around on the circle of life and find nothing new under the sun, while humans escape the monotony and set off on a vector of possibility, destiny and purpose. I would suggest that it is Ball’s definition of meaning that has precipitated the meaning crisis, because when human exceptionalism is reduced to animal mediocrity then humans are relegated to hamsters running on a biological wheel rather than explorers setting off on a road less travelled.

Get access to exclusive bonus content & updates: register & sign up to the Premier Unbelievable? newsletter!

Overthinking the brain

The problem with invoking an evolutionary mechanism to account for the move from dumb to smart, is that it must explain how grammatical DNA mistakes somehow produced profound human literature. Materialists assume that evolution creates minds because that is what evolution does, but it fails to explain why chemicals crave spiritual experience and why matter feels the need to get metaphysical. Ball made the case that the mind evolved so that organisms could better adapt to environmental changes but failed to address its penchant for creating weapons of mass destruction, taking mind altering drugs and falling victim to mental illness. The mind, rather than streamline the evolutionary process, appears to make it less efficient.

Ball recognises the limits of our genome and suggests that “minds are ways to escape our genes” but once you toss out your genes, you have lost your biological innovator and replicator and have given natural selection precious little to work with. The materialist is then forced to overthink the brain and invoke the phenomenon of emergence where neurological complexity confers superpowers that allow the mind to transcend its biology. I, however, find it hard to believe that the chemical proletariat is capable of uniting and overthrowing the genetic bourgeoisie just so it can contemplate its own navel.

Theomorphism

The conventional evolutionary explanation for the mind begins in a warm little pond but ultimately just muddies the explanatory waters. Materialists want to make the mind the epilogue to the book of nature but now find that many in the scientific community believe it should be given the award for best cosmological screenplay. Physicist Sir James Jeans states it like this:

“Today, there is a wide measure of agreement, which on the side of physics approaches almost to unanimity, that the stream of knowledge is heading towards a non-mechanical reality; the Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears as an accidental intruder into the realm of matter; we are beginning to suspect that we ought rather to hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter.”

If Jeans is correct, then the scientific method can be better defined as the process whereby unique creatures equipped with divine voice recognition software rethink God’s thoughts. The only worldview that reflects this understanding is the Judeo-Christian one because it posits a divine person who spoke his mind into the natural world and then created image-bearers who were fluent in lingua Dei.

We need to be cautious when we anthropomorphise God, but we also need to remember that God theomorphised humans. He made us image-bearers, which means that we aren’t just evolutionarily fine-tuned animals but exist on a whole other divine wavelength.

“The Bible is primarily not man’s vision of God but God’s vision of man. The Bible is not man’s theology but God’s anthropology.” (Abraham Joshua Heschel)

Discussions like the one between Philip Ball and Nick Spencer are fascinating, but we must not miss the forest for the trees because once we step back from all the data, we must agree that humans pondering their exceptionality is quite astonishingly exceptional.

Click here to watch The Big Conversation: Can science and religion tell us what it means to be human? and visit thebigconversation.show for more conversations like this.

Erik Strandness is a physician and Christian apologist who has practiced neonatal medicine for more than 20 years.